A Field Guide to Poul Anderson's Tau Zero (1970)

The grand hard science fiction classic he wrote twenty years too early

Contains spoilers for Poul Anderson's Tau Zero, The Butterfly Effect, and Aniara.

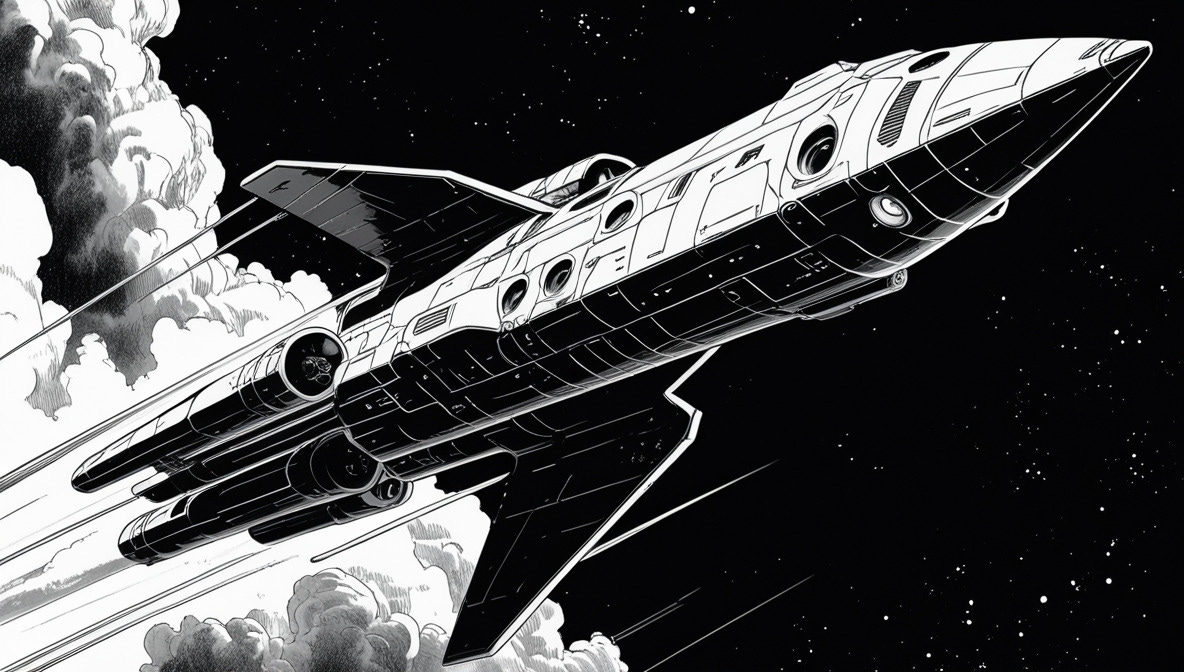

Tau Zero’s premise of a starship with a stuck accelerator snared me. I imagined rigorous science and a broken crew straining to keep their fractured pieces together enough to endure reaching the end of forever. Poul Anderson floated vast and challenging concepts that kept baked 1970s science fiction nerds floating in a haze of what-ifs late at night, as Tarkus spun on the record player.

Books are dimensional portals sliding us into other worlds, but they are less effective time machines. I traveled into the past and remained burdened by modern expectations.

The magnificent concept gave way to a plodding first third that focused on the Leonora Christine’s DeGrasssi High crew arguing over who would be sleeping with whom right up to the inciting incident. I put the book down several times. I had to convince myself that if her crew could commit to the end of time, I could commit to Tau Zero. I’ll leave it to those who have read it to determine which was longer.

The Concept is the Protagonist

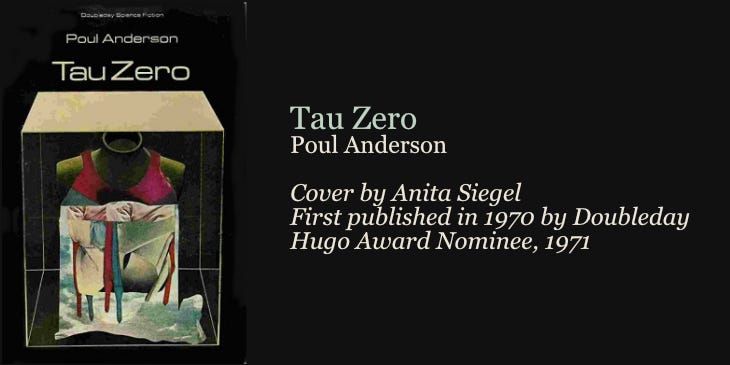

Poul Anderson (1926-2001) was a prolific writer known for his hard science fiction, honed in Campbellian pulp magazines of the 1940s and 50s. He stacked Hugo Awards, became an SFWA Grand Master, and attracted the accolades of peers. Algis Budrys, called him “science fiction’s best storyteller” and Heinlein included him in the dedication of The Cat Who Walks Through Walls (1985).

Campbellian science fiction tended to include themes of the triumph of human ingenuity, exploration of space, and ethical implications of scientific advancements. Stories often celebrated progress and rational thought. Birthed as a short story titled To Outlive Eternity1 in the June 1967 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction magazine, the novelization that became Tau Zero was firmly planted in this style.

By these standards, Anderson succeeded. With few storytelling liberties, the scientific foundation was rigorous for its time. His application of time dilation and relativistic effects showed understanding which lent credibility to the narrative.

As he said in a 1997 Locus interview:

“What five books would I like to be remembered for? Well... Tau Zero, I like that one especially. It was somewhat of a tour de force, and I think it got across what I was trying for.”

Anderson drove the nail straight into the stud but with more force than precision. As a concept, Tau Zero was outstanding, but novelization felt like it had overburdened the framework with front-loaded character development and flat archetypes.

It was published right in the middle of a tug-of-war between Campbellian tradition and New Wave’s focus on character psychology and social commentary that arose in the 1960s.

Harlan Ellison called the Campbellian style a “straitjacket that limits the imagination” while Michael Moorcock said it had a “very narrow view of what science fiction should be”.

Asimov called the New Wave movement “style over substance, lacking scientific rigor” while Heinlein remarked that it was “a fad that will pass”.

This sets the stage for the wide spectrum of opinions you’ll find about Tau Zero. Some see a focus on concept with unremarkable characters while others respect it as a great concept with ambitious character development.

I respect it as one of the grandest concepts of science fiction. But also, marred by character development that is not rich enough to independently support the entire first third of the story. It is the weaker combination of both worlds: too much focus on characters to maintain conceptual momentum and too little development to make those characters compelling.

I can only attribute this to the process of novelizing a short story, because Anderson created enjoyable characters in The High Crusade (1960). That story does not use the first sixty pages to establish characters as a primary pillar. It is 10,000 words slimmer and ninja runs into the inciting incident, establishing characters alongside the story.

The Promise of Universal Death

“In our immense sarcophagus we lay

as on into empty seas we passed

where cosmic night, forever cleft from day,

around our grave a glass-clear silence cast.”

— (Martinson, Aniara, Canto 103)

Fitting the entirety of time into a couple hundred pages is audacious. The starship Leonora Christine is damaged and cannot decelerate. Her crew becomes helpless. They approach the speed of light, and eons compress into moments. Mankind’s remnants are imprisoned to witness cosmic evolution and fated to experience the universe’s collapse.

Aniara2 is a 1956 epic poem by Swedish Nobel laureate Harry Martinson. It beautifully explores the same theme, but in his epic, the ship and its passengers are forever lost in space. The crew reflects on the futility of their situation and concludes with a melancholic resignation. A meditation on mankind’s search for purpose that finds no answers.

Anderson may have conceived of Tau Zero as a response to Martinson’s bleak vision. In his, Leonora’s enduring crew find new purpose in a fresh universe. But if Anderson desired to portray hope where his inspiration found despair, his characters were incapable of shouldering that thematic weight.

Anderson could have created something unprecedented by grounding existential terror in real physics. What happens in a universe with no big crunch? Who breaks as the universe idles forever in the spiral of heat death until the decay of every proton? And how? What are the thoughts of the last conscious thing in existence? Instead, he steers away from truly unsettling implications. He buries the potential under surface-level interpersonal drama from the very beginning and it never earns its place.

Later, his writing transitioned to a more pessimistic perspective on human nature. Tau Zero still embodied the optimistic and adventurous themes characteristic of his Campbellian subgenre. Later stories reflected a more nuanced view on humanity. It can be seen in works like The Boat of a Million Years (1989) and The Last Viking (1989), where he charts the complexities and darker aspects of human existence.

When I picked up Tau Zero, I wanted the story an older Poul Anderson might have written. The one with the more complex characters which might not have pulled punches in the ending.

Summer Camp Hookups in Space

Mankind sets out to colonize and populate its first planet in the greatest starship ever built. Minimal thought seems to have gone into planning how they would actually populate their new home on Beta Virginis (Zavijava), though. As First Officer Ingrid Lindgren explains: “Twenty-five men and twenty-five women. Five years in a metal shell. Another five years if we turn back immediately... we’ll pair off.”

That’s it. There does not seem to have been any planning or arrangements prior to assembling the crew or any thought given to the genetic diversity they would need. They packed a college class worth of crew members on a ship and left the rest to Jose Quervo.

Given this, the relationship drama does not even emerge from cosmic pressure. It starts during early routine mission. Before any crisis hits, crew members fret over romantic partners.

These elite scientists approach an interstellar mission like hormonal teenagers, worried about summer camp hookups. Crisis transforms the mission from exploration to exile but does not sway this focus. It provides a new context for the same relationship anxieties.

Even viewed as simple archetypes, these characters seem disconnected from the monumental stakes:

Psychologist soothes the crew but is never used to explore their profound psychological toll. How do you guide fifty people experiencing real existential dread? How do you, with the tool-set of an earthbound profession, face it yourself?

Security chief barks orders to maintain discipline, a role that remains static whether the problem is a broken machine or the end of reality itself.

Captain makes stoic decisions, but the narrative shines no light on his immense burden. How do you lead when there is nothing left to lead your crew to and no option for retreat?

Each character performs their job, but none truly inhabit the story.

The story attempts to serve two masters. It explores the changing sexual mores of the decade while holding on to its plot-driven, concept-first roots. However, the characters remain too archetypal to plumb the depths these explorations. The concept remains the focus, but the lacking character depth makes these relationship elements seem more pronounced, longer, and harder to trudge through.

The ambition of this approach is not matched by execution. Anderson gave his characters enough development to make their shallow treatment unsatisfying while devoting enough time to them to slow the story’s conceptual momentum. It represents the structural contradiction at its heart. Stalled in a narrative Lagrange point between Campbellian efficiency and New Wave psychology that satisfies neither.

When Cosmic Becomes Routine

Ironically, once the ship’s acceleration crisis begins, Tau Zero fails to match it. Instead, it settles into its cycles of crisis: crew despairs, makes a new plan, plan fails. The sense of these iterations lacking variety and escalation is mostly driven by weak characters with minimal transformation, which is necessary for them to become meaningful.

The relationship drama continues throughout. Universal collapse serves as staging for romantic triangles. When Anderson writes, “They talked business for half an hour. (Centuries passed beyond the hull),” he reveals how cosmic scope becomes mere background to soap opera melodrama.

The emotional responses of the crew are inconsistent. They bicker over romantic partners one moment, then calmly discuss the heat death of the universe the next. Moments meant to convey existential dissonance become comedic: “My God—very literally, my God—we’re not supposed to be having regular bowel movements … while creation happens!”

This is a consequence of certain structural choices. Front-loading character drama without proper development leads to whiplash when shifting to genuine existential terror.

The Cosmic Horror Anderson Didn't Write

I had meant to make them an Edenic place,

but since we left the one we had destroyed

our only home became the night of space

where no god heard us in the endless void.

— (Martinson, Aniara, Canto 102)

Tau Zero’s ending mines under its own premise. After building toward the ultimate cataclysm, they are gifted miraculous salvation in an act of deus ex machina. The stage hands lower one of the gods from the rafters, guiding the crew to an improbable resolution where they not only survive universal collapse but find a new Earth-like home on their first try. Anderson walks the line of cosmic horror but refuses to commit to its implications. He sidesteps the fundamental questions about human meaning and mortality that witnessing universal death demands.

The ending suffers the dissonance also found in The Butterfly Effect (2004). The theatrical cut feigns a naturally dark conclusion, leaving the protagonist, Evan, a double amputee. Instead of ending there, it continues for twenty minutes. Evan has one more attempt to patch the temporal chaos.

He succeeds, but he and his love interest are now strangers. There is no childhood meeting. They do not grow up together. The film delivers a manufactured, bittersweet resolution, where they cross as strangers on a crowded street, sense something, dismiss it, and carry on. In the novelization, it is the same, but Evan invites her to coffee.

But there’s another version. A director’s cut that gave The Butterfly Effect its rightful conclusion. An ending consistent with and demanded by the story. Evan travels back in time and strangles himself in the womb with his own umbilical cord.

Both Tau Zero and The Butterfly Effect earn brutal endings but pivot to an unearned finale disconnected from their journeys.

This approach is not without its defenders. Stephen Baxter, a physicist and fellow hard science fiction author, saw it as a feature of the tradition Anderson was writing in. Baxter wrote in his afterword to the 2006 edition of Tau Zero:

“The characters are types. But that’s the point... Anderson is in the American pulp tradition of John W. Campbell’s Astounding, where the key was to get on with the story, to get to the next idea.”

This fairly assesses Anderson’s intent and his era’s narrative priorities. However, it does not excuse the structural problem. Even by this standard, Anderson failed to “get on with the story.” He buried his concept under significant underdeveloped character interactions.

The premise naturally suggested a different approach, where the reader experiences the existential stakes and terror through psychologically complex characters with whom we empathize. This could have delivered a view of a decaying cosmos that felt like more than theme-park vignettes.

Scale and Consequence

Tau Zero offers a lesson about scale in storytelling. When your backdrop is the death of a universe, your narrative choices should match that magnitude. Anderson’s concept is compelling, but robbed of impact by thin characters and reduced to triviality through structural contradiction. A story of this magnitude should make its characters more than passengers; they must be worthy of the apocalypse.

Anderson is a masterful writer whose work I admire. In a historical context, Tau Zero succeeds as intended, but a modern reader senses the starkness of a missed opportunity. The cosmic horror version of this story, which could have explored how people endure and are transformed as witnesses to a dying universe, remains unwritten.

I discovered Tau Zero almost a year into plotting my novel which shares a similar premise. Watching another author grapple with the grandest of concepts affirmed my direction. Anderson has sharpened my resolve to explore the psychological terror inherent in watching the end of everything from a lonely cage outside time.

Field Notes

Tau Zero’s entry at The Internet Speculative Fiction Database

Detailed biography of Anderson at The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction

Tau Zero’s plot, publication history, and reception on Wikipedia

Rich analysis of Tau Zero in a 2014 review by James Davis Nicoll

Divergent Readings

One mark of a classic is its ability to support different interpretations. While I read Tau Zero as a structural flaw:

Marcello makes a passionate case for the novel as a psychological success in his essay on Substack.

Theodore Beale’s thematic analysis celebrates character drama as the source of the book’s strength in an essay at Black Gate.

Coming next month: Pier 99

To Outlive Eternity was published in the June 1967 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction. The issue is available to read at the Internet Archive, though the Poul Anderson story, itself, has been removed at the request of his estate.

The Ariana stanzas are from the 1999 English translation from Swedish by Stephen Klass and Leif Sjöberg. A digitized version of this translation is available to read at the Internet Archive. For general background on the epic poem and its Nobel laureate author, see its entry on Wikipedia.